NXP technology history is a goldmine for artists

Chip manufacturer NXP wants to keep the history of technology alive. So they asked students from the ArtEZ University of the Arts to use old technologies and machinery as inspiration for art.

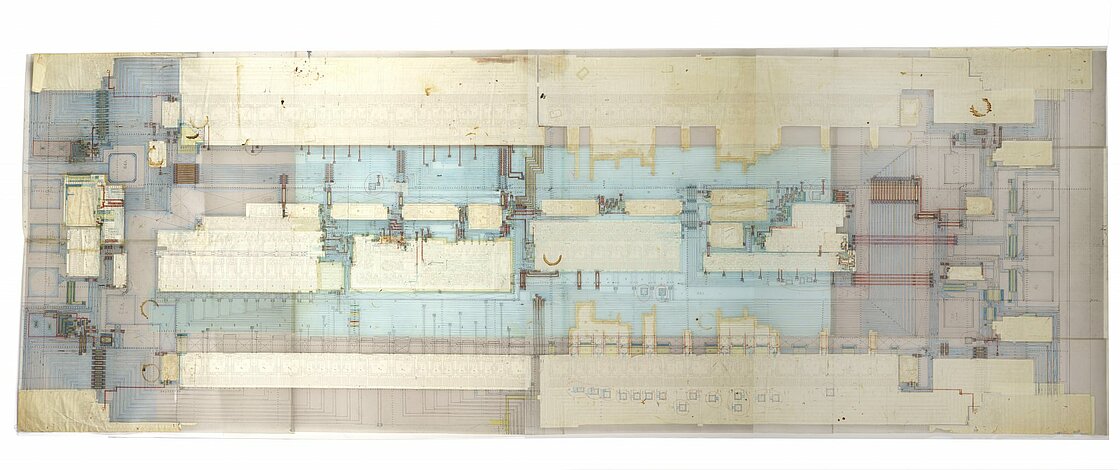

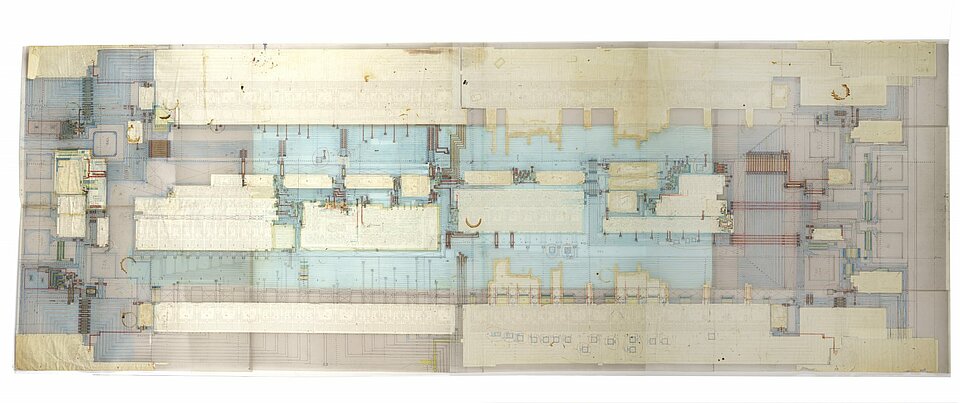

The Dutch city of Nijmegen was home to the first semiconductor factory in Europe; in 1953, Philips started assembling semiconductors here. Nowadays the basement of the current NXP building house a large collection of machinery and old technologies. From diodes to the first memory chips, which were made by hand. Or a meter-sized drawing, a kind of subway map, on which the infrastructure of the very first chip is drawn in detail.

Gathering dust

It would be a shame to let all that history gather dust or even be thrown away. Over the past decades, group of volunteers, mostly made up of retired former employees, have devoted themselves with heart and soul to the collection. “At the same time, it begged the question of what we should do with it all,” says Jan-Paul Kimmel, social responsibility manager at NXP in Nijmegen. “You can store a huge collection of gear which all has a great story in the basement, but what good is that?” So, how do you translate technological history into something that is simultaneously engaging and inspiring to look at?

Goldmine

With this in mind, NXP decided to approach the Design, Art & Technology study program at ArtEZ University of the Arts in Arnhem. A group of students then came to take a look. “A goldmine! We immediately how urgent it was to preserve this, although we really had no idea what exactly a lot of these apparatuses and parts were meant to be,” says Florian van Zandwijk. He was at the time a fourth-year student at ArtEZ. “But this is where the digital revolution in stories and equipment was up for grabs.”

Graduation project

NXP and ArtEZ decided to join forces, and so the fourth-year students got to work. Their internship at NXP became their graduation project. The former employees explained how the technology works and about the things that can be seen. And the students translated this into an installation that showcases the technology and allows it to be experienced. That prompts and clarifies much more than simply displaying the old materials to the public.

“Here lies the history of our technological progress.”

Florian van Zandwijk, former Artez student.

XL Chip

“Technology used to be much more visual than it is now,” says Bram de Groot, Van Zandwijk’s fellow student at Artez. “Human craft and ingenuity led to super-fast chips at a level of abstraction that we can hardly grasp anymore. The chips that are now in minuscule formats in almost all electronic devices used to be made by hand. It was painstaking work where different raw materials such as gold and copper were soldered onto a plate.”

De Groot decided to recreate these first memory chips in bulk. He used beads as separate bits and connected them together with wires. A kind of XL chip. “A lot of these old techniques are of great artistic beauty,” he noted.

Impact of technology

The high-tech industry in the Netherlands is of the highest level. Van Zandwijk: “It has defined our infrastructure, the way our country is structured. There is so much that can be said about it. It is the history of our progress and you have to preserve that properly.”

Van Zandwijk wanted his installation to show the impact of technology on society. “I looked at the ethical side more than the technical side. What can we do today, but also what are we unable to do with super-smart technology? Can image recognition software tell what that person’s intention is from the yellow vest that they are wearing? Does that person have car trouble or are they demonstrating against the system? As human beings, we are capable of making this distinction, but is a chip capable of doing that as equally well? I thought this was an interesting thought experiment.”

LINK Foundation

The students’ art installations caught on and were exhibited at NXP. This proved to be the beginning of more to come. “The collaboration with ArtEZ is a valuable link that has inspired us to make our materials more visible,” Kimmel points out. A special foundation – the LINK Foundation – was recently set up with the aim of bringing together NXP’s historical collection and the art installations of ArtEZ students.

ArtEZ exhibition

Van Zandwijk is also a member of this foundation, as are several (former) employees. “I’ve since graduated. But I find it really fascinating to think about how we can make this history of technology accessible in an engaging way through art. Artists are ideally placed to make this kind of translation. The conversations that arise with employees and interested parties about the impact of this industry on the world are extraordinarily surprising.” The municipality of Nijmegen is enthusiastic as well. Kimmel: “Together, we are thinking about exhibitions. Temporary or permanent, we are not sure yet. But in any case, we will put more work into it.”