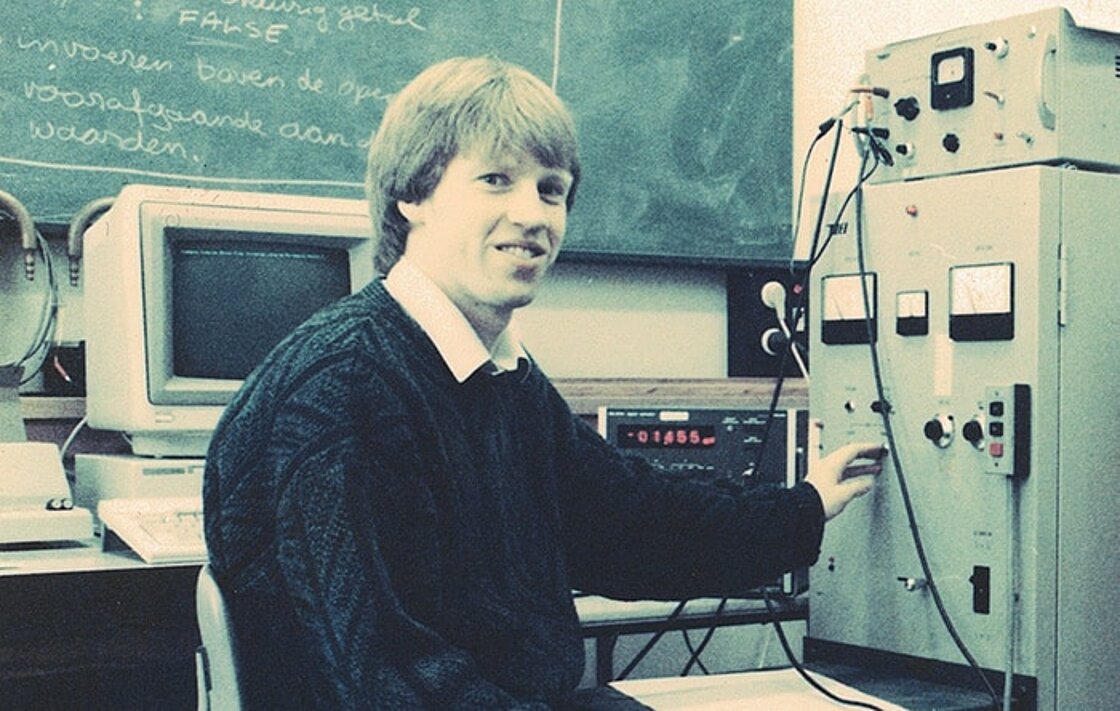

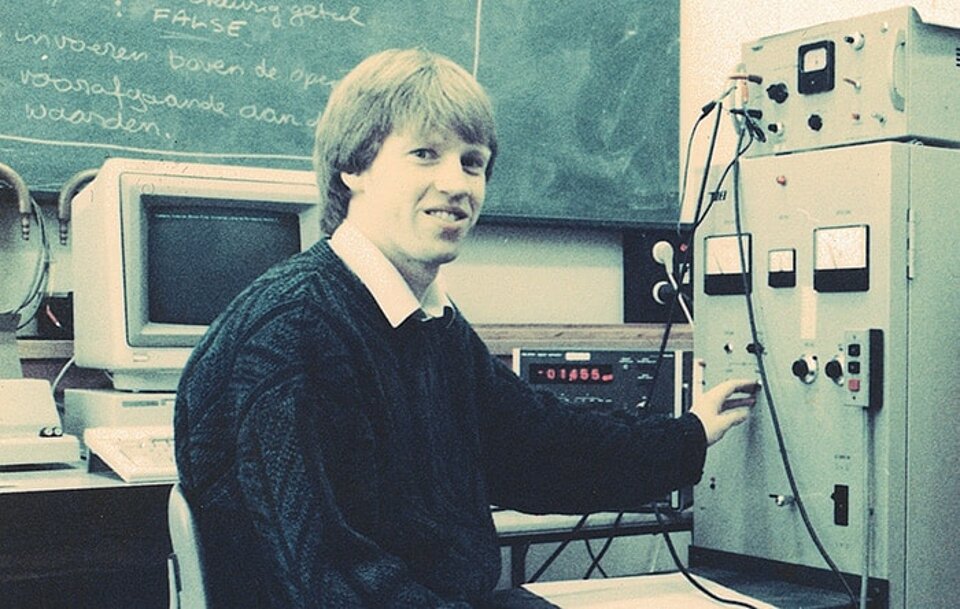

Mark Johnson, the man of hundreds of patents: "There is no training to become an inventor"

Philips invests nearly 10 percent of its annual revenue into Research & Development; in 2020, this amounted to 1.9 billion euros. Of this, 40 percent, roughly 700 million euros, goes to Eindhoven, which is the most important and largest innovation hub of Philips worldwide.

Inventing the world of tomorrow, that is what people at Philips work on every day. In 2020 alone, they filed 876 patent applications with a strong focus on health technology and services.

The ground-breaking work of inventors will determine Philips' future success. But how do you make sure that the innovations you bring to market successfully truly impact healthcare? “There is no training to become an inventor. You can only become one through experience and by being open to new ideas.”

There is no training to become an inventor. You can only become one through experience and by being open to new ideas.

Mark Johnson

Mark Johnson should know; as a Research Fellow he is not only responsible for a record number of patents within Philips, but supports fellow researchers in following the path from idea to intellectual property on a daily basis.

How long have you been active at Philips?

“I came here as a physicist about 35 years ago. Initially, I worked on magnetic materials used to store information on video tapes, among other things. In the early 90s, I had the privilege of working closely with two later Nobel Prize winners, Peter Grunberg and Albert Fert.

They invented the giant magnetoresistance (GMR), a foundational sensor technology for miniature hard drives consisting of magnetic material, which eventually enabled the creation of devices like the iPod. In 2007, they received a Nobel Prize for this invention.”

“After that, I ended up in a different division within Philips, which dealt with displays. That is where I discovered Philips is home to some top-notch inventors. You have to imagine; there are about twenty different types of screens available in the world, such as LCD and plasma screens. One single Philips researcher invented three of the twenty types of displays available. I thought that was unimaginable, and actually I still do.”

“You could say that my fascination with patents started then; that is when I really started inventing.”

Within Philips, Invention Awards are given to researchers who were granted 10, 25, 50 or 100 patents. How many were you granted so far?

“I find that difficult to determine since it is not a competition, but I can say well over five hundred. By the way, did you know that Thomas Edison, the nineteenth century inventor, is still in the all-time top ten in terms of number of patents granted? He had 1,084 of them. However, what was true for him is certainly true for me; a patent is almost always filed and granted together with a team. I have a few that have only my name on them, and they are certainly not the best.”

Philips has transformed into a health technology company. How is that reflected in your research?

“Slightly over ten years ago, when Philips started to focus entirely on health technology, I began working on the development of smart devices and sensors to measure vital signs of patients, among other things.

I think the largest difference lies in the shift from hardware to complex systems. It used to be relatively clear; we developed a device that was patented and then marketed; a display, toothbrush or MRI system. Philips has always been good at patenting a new device, which is very important, because a patent is a necessity for successfully marketing a new product.

Today, the way we develop products is changing drastically; our systems are becoming increasingly digital, and it is important that they work with other systems as well. The demands for patents are changing. We no longer simply develop standard solutions, but we co-create them together with our customer to meet their needs as much as far as possible.”

We co-create these together with our customer to meet their needs as far as possible.

Mark Johnson

Today, you are helping research colleagues from all over the world apply for patents. How did you start doing that?

“Before, applying for a patent was frankly a bit of an ad hoc process which everyone did in their own way. We then invited consultants to train ourselves. That is when we found out that, as a team, we already mastered the process better than the consultants did. However, we still had to record the way we apply for patents in a repeatable process. ”

"We recorded the process and now I work with a global team to support colleagues across the globe in applying for patents."

According to you, where lies the secret of Philips' innovative strength?

“On the one hand, we have a long history of standardization, and you can hardly underestimate the importance of this within technology. Whether it was the development of CDs, DVDs or MPEG files; Philips has always helped build global standards. Especially now that technological ecosystems in healthcare are becoming increasingly complex, standardization is extremely important, because it ensures that different systems can be seamlessly connected to each other.

Philips has always helped build global standards.

Mark Johnson

To this end, as Philips, we can have experts from various disciplines join each innovation process; whether in the medical field, such as a general practitioner, psychologist or oncologist, or in the technology field, such as hardware and software experts, data scientists or AI specialists. Because we have so many disciplines within our company, we can create innovative solutions that help solve real problems.

Finally, and I think that is the most important thing: it is in our culture, from the laboratories all the way to the top of the organization, to share knowledge and thus collaborate on innovations."

It is in our culture, from the laboratories all the way to the top of the organization, to share knowledge and thus collaborate on innovations.

Mark Johnson

What advice would you give to young colleagues who want to make it in R&D?

“Make use of your training, but be prepared to broaden your horizon as well. If you get an opportunity to do so, seize it. An open mind is the greatest gift you can get as an inventor. Always look for opportunities and not for problems. Of course there is always a time to be critical, but usually it is better to be more constructive and think along positively. ”

Within Philips, every day thousands of inventors work on tomorrow’s technologies. What drives them? How do they come up with their ideas and how do they successfully bring them to market? In the Impactful Inventors series, we will answer these questions.