Being a researcher and entrepreneur means playing chess on several boards at the same time

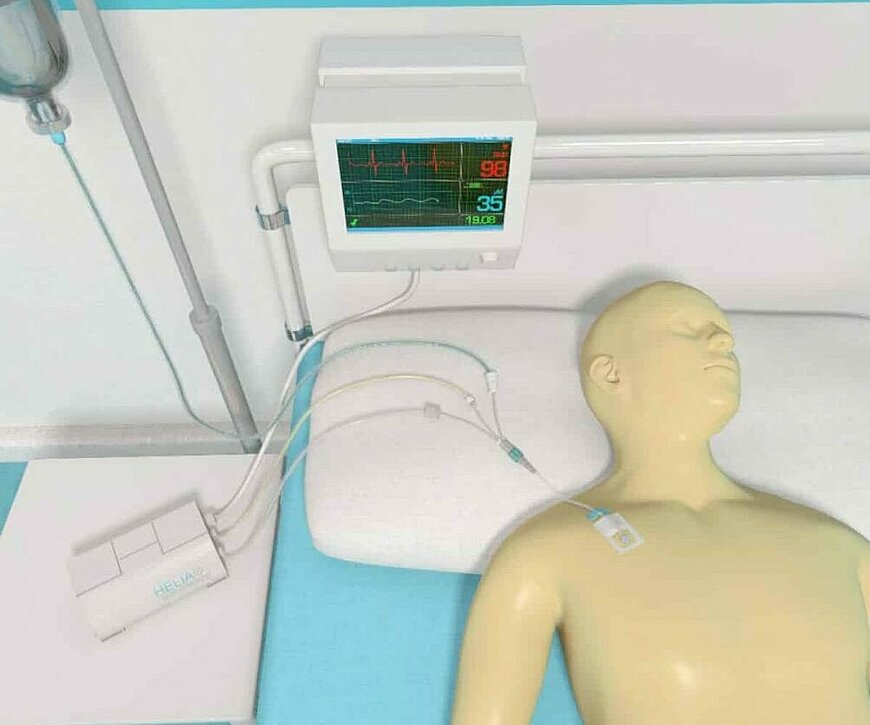

Thanks to a new biosensor, medication doses can be automatically regulated based on a patient's condition. Lives can be saved by continuously monitoring the concentration levels of medicines in blood.

Helia Biomonitoring, a spin-off of the Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e, the Netherlands), is currently working on the development of new biosensors. “Sensors already exist that continuously measure glucose levels, which is a godsend for people who have diabetes,” says Menno Prins, co-founder of Helia Biomonitoring. “But there are plenty of other substances that we want to continuously monitor.”

Menno Prins

Traditionally, samples are taken from patients periodically, e.g., with a test tube of blood. These are then sent to a laboratory and a single test result is obtained from each sample each time. Often a long period of time passes between successive measurements. It would be a good idea to take continuous measurements so as to improve treatments. “It is often difficult to dose medications correctly for patients in intensive care who have infections. Too low a dose does not treat an infection and too high a dose can be toxic. The dose needs to be adjusted dynamically, and furthermore the adjustments vary from person to person. That’s what makes continuous monitoring so important,” he explains.

In addition, the biosensors can also be used to measure inflammation biomarkers. “Consider, for example, measuring cytokines that also play a role in COVID. A patient can die if their immune system becomes disregulated. If you were able to measure these inflammatory substances continuously, you would then be able to act more quickly,” Prins says. The sensors would then have to be capable of measuring low concentrations very accurately. “This is possible, but it still needs a lot more research,” he adds.

From company to university

Prins came up with the idea of researching continuous biosensors when he was still working at Philips. Back then, the subject was still in the exploratory phase and was distant from the market. That’s why Prins made the move to a university. “I was already working part-time at the university and saw that there was a lot of interest in this subject among the students and staff members. This allowed me to fully immerse myself in the technological challenges and application areas,” he goes on to say. “It turned out that biosensors can be extremely beneficial to society in a variety of ways. Since then, the technological research has been well developed, patents have been applied for, funding has been raised, and subsequently the Helia Biomonitoring company was founded. That’s two years ago now.”

A lot of research and validation is still needed before the sensors can be rolled out in the healthcare sector. Which is why Prins has drawn up a roadmap for the technology and its applications. The first application area for the sensor will be in the food industry. Industrial processes can be precisely monitored and automatically controlled using Helia Biomonitoring biosensors. Prins: “This means that processes can be fine-tuned more accurately. This guarantees a stable level of quality for products, less waste, and lower levels of energy usage.”

Plant-based proteins

An important area of application is in the extraction and purification of proteins from plant-based sources. More and more foodstuffs have plant-based proteins as essential ingredients. One of these ingredients is potato protein. This protein is qualitatively similar to the protein of a chicken’s egg. In order to extract this protein from potatoes, processing steps are used that are as careful as possible so as not to impair the fragile structure of the protein, while at the same time removing any bitter-tasting substances. “Continuous monitoring of the biochemical parameters makes it possible to optimally control these processes,” Prins explains.

TU/e and Helia Biomonitoring have been granted funding from the Dutch Top Sector Policy. “It involves three top sectors, namely Agri-Food, Chemicals, and High-tech Systems and Materials. It really is quite special that these top sectors have come together in one project,” says Prins. “This means we can really get to work on this together with partners from the food sector. We will be carrying out research, developing prototypes and conducting tests with our industrial partners.”

Bioreactors

One step further on the roadmap is the application of the sensors for bioreactors and fermenters. “Increasingly more innovative production methods make use of living cells. These include microorganisms and animal cells. These are used in the production of food, chemicals, medicines, and entirely new products, such as cultured meat.”It is essential to monitor fluctuations in these biological processes and adjust things accordingly. Another application is the use of biosensors in the environment. For instance, to measure drug residues in wastewater and surface water. On the roadmap, medical products will be the last to be made available. “Developing medical products costs a great deal of time and money owing to the high standards for patient safety, accuracy and ease of use. That is why it is prudent to develop and validate as much as possible the sensor technology along with any other applications.”

New research

He goes on to say: “The technology is suitable for monitoring and regulating dynamic biological processes. You can use the sensors to measure substances and immediately adjust these processes where needed.” The steps that Prins is taking to further develop the biosensors are aimed at impacting society. The partnership with the university is indispensable in this respect. Bart Nelissen, Business Developer at TU/e Innovation Lab, sees considerable value for the university as a consequence of this collaboration. “Helia’s work is generating new ideas for research and other applications. This in turn leads to new directions in research at the university,” he goes on to explain. “The company can later use some of the results to develop prototypes or products.”

The collaboration between the young company and the university yields scientific research projects that they can jointly apply for funding for. “The trend nowadays is that you have to be able to indicate very clearly the potential impact of your research. This is extremely concrete with a company like Helia Biomonitoring on board, and improves the chances of success for a research application,” Nelissen points out. The university also has a stake in the company, although this doesn’t necessarily mean that income is immediately generated, according to the business developer. “This is more for the long term, whereas the funding for joint research projects can be used immediately.”

Researchers as entrepreneurs

What makes Helia Biomonitoring all the more special is that Prins, as a researcher, also manages the commercial part of the spin-off. “If a research project is so far that it can be commercialized, then we have several options,” Nelissen says. The university could work with an existing company to see whether they can actually roll out the technology. Or a spin-off might be set up. He points out that: “The latter was the case with Helia as it soon became obvious that large companies still considered it too risky to start working with it.”

Prins continues: “We first looked at whether an experienced entrepreneur would be able to lead the spin-off. But in discussions with partners and financiers it became clear to us that having an understanding of the technology was essential,” he says. “That’s why I decided to delve into it more and make the leap to entrepreneurship.” Sometimes entrepreneurship can be difficult. “You have to be able to play chess on several boards at the same time and communicate clearly with everyone. I’ve learned to quickly consult experts whenever I am stuck. It’s really surprising how many people are willing to help a spin-off.”

Nerve

Prins now works for Helia one day per week. “That shows that he’s got plenty of nerve,” says Nelissen. “Menno knows both the industry and the university and is now combining these two worlds to raise his ideas to the next level.”Nelissen says he encourages researchers to see if they themselves can manage a spin-off. “Sometimes it’s better to hire someone from outside in order to get a spin-off off the ground, but I think researchers should be given the opportunity to do it themselves. You learn so much from doing that and it inspires other researchers to one day take the same step.”

Helia Biomonitoring is set to take off in 2021. A funding round is coming up, the company is going to expand and on the lookout for its own premises. “We want to stay close to the university because that will be better for the collaboration,” Prins states. “The ultimate goal is to use new sensor technologies to change the lives of lots of people in positive ways.”